Note: The maps in the book are in black and white. Lower resolution colour images are used here for clarity.

Attica is currently the wealthiest and most densely populated part of Greece. It consists principally of a number of interconnected plains, floored by alluvium and Pleistocene sediments, and cut off to the north-west by the great mass of Mt Parnes (figure 3.1; Plate 3A). The Central Plain around Athens is bounded on the north by Mt Parnes, on the north-east by Mt Penteli, on the south-east by Mt Hymettos, and on the west by Mt Aigaleos. It connects with the smaller plains of Marathon on the north-east, Eleusis (the Thriasian Plain) on the north-west, and the Mesogeia on the south. The indented coastline provides a number of good harbours, of which Piraeus is by far the best. There are few rivers, apart from the Kephissos and the Ilissos, which run through Athens partly underground; all are dry in the summer.

The soil is generally poor. It is unsuited to stock breeding and, in general, to agriculture, except for olives, vines and figs. The territory is, however, rich in limestone and in the marble of Mts Penteli and Hymettos; in addition, there was formerly (until it was worked out) a copious source of silver and lead in the hills of Lavrion. Finally, Attica was (and is) blessed with generous supplies of potter's clay, to which the Athenians surely owed their pre-eminence in the craft of pottery. The best clay came from deposits near Athens, especially at the northern suburb of Amarousi (where it is still worked), and on Ayios Kosmas (ancient Cape Kolias), near the present airport (ref 130).

In early times Attica was made up of a number of independent communities. There is probably an element of truth in the legend that they were brought under Athenian control by the hero Theseus at about 1300 BC; but the process was probably not completed till the seventh century BC. Thereafter, the history of Attica is inextricably bound up with that of Athens.

The geological structure of Attica, as in much of Greece, is dominated by a series of nappes stacked up during Alpine compressional movements. The oldest rocks in the region occur in one of the higher nappes along the north-west borders of Attica, in the mountains of Aigaleos and Parnes. These mountains are dominantly made of Triassic limestones of the Pelagonian Zone similar to those occurring as far north as Thessaly and western Macedonia.

The southern and eastern parts of Attica are underlain by schists and marbles of the Attic-Cycladic Metamorphic Belt similar to those in southern Euboea and the Cycladic islands. These marbles make up Mts Hymettos and Penteli, as well as the hills around Marathon and Lavrion.

The next highest nappe is made of schists, cherts and ophiolites, which is in turn overlain by lightly metamorphosed and unmetamorphosed limestones and flysch sediments of Cretaceous to Eocene age. The uppermost part of this series is called the Athens Schist (see below) (ref 173).

During the Neogene period compressional forces associated with Alpine mountain-building ceased. Erosion and faulting produced a series of basins which were flooded by the sea and filled with sandstone, shale, clay and limestone. These rocks are still in their original places of deposition, except that they have been raised above sea-level by geologically recent tectonic movements.

The site of Athens has been inhabited for approximately 8000 years, and

from at least the beginning of Mycenaean times, around 1600 BC, it has

been one of the greatest cities of Greece. Like Mycenae and Tiryns,

Mycenaean

Athens possessed Cyclopaean walls, a monumental entrance, a postern

gate,

a royal palace, and a secret water-supply. It is also to this period

that

the legends of the exploits of Theseus refer.

The site of Athens has been inhabited for approximately 8000 years, and

from at least the beginning of Mycenaean times, around 1600 BC, it has

been one of the greatest cities of Greece. Like Mycenae and Tiryns,

Mycenaean

Athens possessed Cyclopaean walls, a monumental entrance, a postern

gate,

a royal palace, and a secret water-supply. It is also to this period

that

the legends of the exploits of Theseus refer.

Around 1000 BC the Dark Ages were coming to an end in Athens, and the city became increasingly prosperous, reaching a climax between 600 and 500 BC. During much of this time Athenian pottery was the best in Greece and was widely exported for some 700 years. Another source of wealth was the silver from the mines at Lavrion, especially from about 500 BC. In 490 and 480 the Athenians defeated attacks by the Persians at Marathon and Salamis. Then followed fifty glorious years, which included the rule of the great statesman Pericles. But the Peloponnesian War, 431-404 BC, broke the power of Athens for ever. Henceforward, whether under Hellenistic or Roman rule, Athens, though artistically and intellectually pre-eminent was politically reduced to the second rank. Neglected by the Byzantines, it regained a little authority under the Franks after the Fourth Crusade of 1204, but sank even lower when the Turks invaded in 1456. In 1834, however, Athens was designated capital of the newly liberated Greece.

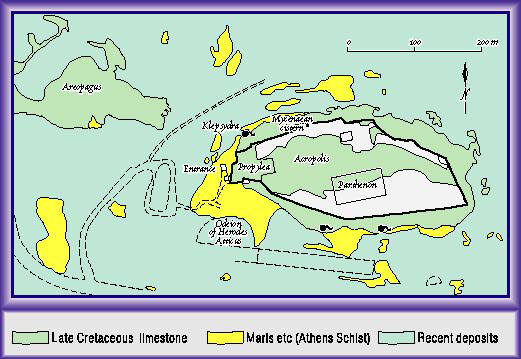

The city of Athens stands in a great topographic basin surrounded by Mts Parnes, Aigaleos, Penteli and Hymettos (figures 3.1, 3.2). This basin was formed partly by faulting and partly by the erosion of the soft 'Athens Schist', which outcrops or underlies the veneer of younger sediments in much of this area. The Athens Schist is a slightly metamorphosed series of Cretaceous marls and shales, with lenses of sandstone and limestone. It is not a true schist by modern English usage (Reference 173).

Many of the hills in the eastern part of the Athens basin, such as Lykabettos hill, the Areopagus, the Acropolis and the Philopappos hill, are made of Late Cretaceous limestones (figure 3.2). There is some debate about the geological position of these rocks, but most geologists consider that they are the upper part of the Athens Schist series of rocks. They may not have been originally continuous over the area and minor tectonic movements have detached these stronger blocks from the weak underlying marls of the Athens Schist. Steep faults have since then dissected the limestones into smaller blocks.

The Athens basin contains a number of different Neogene sedimentary rocks originally formed in shallow lakes, such as limestones, marls and clays. The clay deposits were the basis of the ancient Athenian pottery industry, and are still exploited today. Finally, much of the central and western parts of the basin have been covered with a layer of alluvium up to 20 m thick. Much of this deposition occurred during infrequent floods in the recent past.

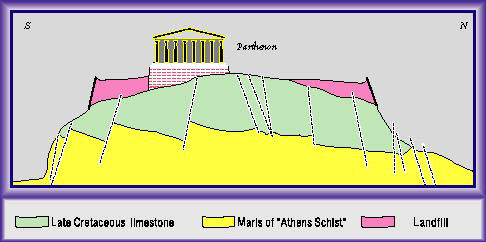

The Acropolis hill is a block of Late Cretaceous limestone resting on

the

marls and sandstones of the Athens Schist rock series (figures 3.3,

3.4),

which can be seen on the approach to the main entrance to the site, and

just beneath the Propylea (References 9, 10, 264). The grey limestone

is

well exposed on the top of the hill. It has closely spaced joints and

some

of the older fissures have been filled with red marl or coarse calcite

crystals. The top of the Acropolis hill has been leveled with

artificial

fill up to 14 m thick which is retained by the walls.

Rainwater seeping into the faults and fractures on the upper part of the Acropolis has dissolved away the limestone to form caves and clefts. Such caves can be seen in the north-west and southern slopes of the hill (Plate 3B), but others, probably mostly choked with debris, undoubtedly exist in the interior of the hill. Much of these percolating waters do not penetrate the underlying marls, which are less permeable, but reach the surface at a number of springs around the base of the hill. One such spring, the Klepsydra, originally issued from a small cave in the north- west cliffs and attracted Neolithic settlers to the area. It was in constant use thereafter and has been subsequently considerably modified.

Towards the north-western part of the Acropolis percolating waters have

enlarged a fault in the limestone to produce a cave or cleft about 35 m

deep. Percolating waters fill the base of this cave to a depth of

several

metres, but the rate of inflow of water is low. The water level is

about

4-5 m above that of the Klepsydra spring to the west. The Mycenaeans

constructed

a means of access to this water source but appear to have used it for

only

25 years or so before it was abandoned. It is possible that the rate of

inflow was too low to be useful.

Flow from these springs was probably stronger in antiquity. This may reflect climatic change, but is more strongly controlled by modifications to the geography of the hill. In the past the presence of plants, soil and loose materials on top of the bedrock would have retarded run-off so that the water could have time to be adsorbed. Recently, infiltration has been all but eliminated by sealing all the open cracks and fissures on the hill with cement. This has been done to reduce the rate of erosion, now enhanced by acid rain.

The sacred hill of the Acropolis was never defaced with quarries, but limestone for many of its buildings and the walls was quarried from several of the adjacent hills including the Hill of the Nymphs (References 57, 290). The foundations of many of the buildings on the Acropolis were made of limestone from Piraeus (see below) and Aegina. Marble from Penteli was used for the construction of all the great buildings of the fifth century, including the Parthenon (see below). Limestone and conglomerate from Kara, near the base of Mt Hymettos (see below), were also extensively used.